“[We] can calculate the motions of the heavenly bodies, but not the madness of people.”

Sir Isaac Newton after losing a fortune from investing in a hot stock c. 1720

Since Putin has chosen to invade Ukraine, 44 million Ukrainians wonder what it means, and so does the rest of the world. Are we returning to a 1980’s-style cold war, as well? The 1980’s saw stocks and bonds return a whopping 17% and 12%, respectively, during an average annual inflation rate of almost 5%. But what will happen this time?

To be sure, much human tragedy is coming from this war. Meanwhile, countless investors from around the globe wonder what this all means economically, and what they should do. While acknowledging the former human questions are of a much higher order, this commentary will focus on the economic implications of the crisis. We direct the interested reader to the Economist Magazine and NPR, among other thoughtful news outlets, for some helpful analysis on the human situation in Ukraine.

What impact will the invasion have economically?

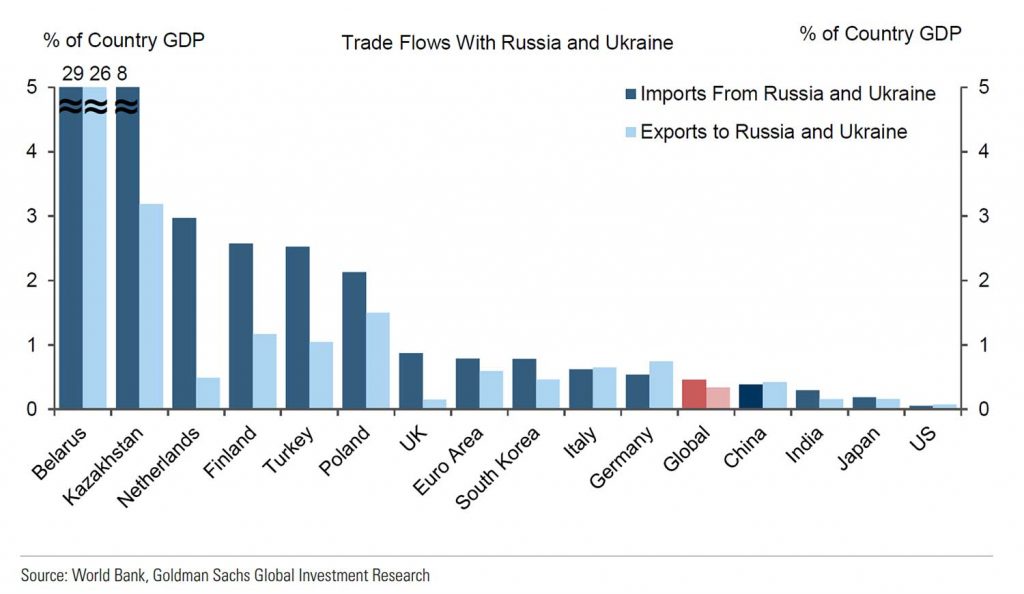

In terms of direct economic impact, the Ukraine conflict will likely have little impact, especially on the United States. Primary direct global economic impact comes through international trade flows, which are measured by exports and imports. That is, the amount of goods and services a country might be selling to Ukraine and Russia, and what amount of goods and services that same country might be purchasing from these two countries. The below chart provides these current figures as a percent of the total economy (i.e., GDP) for the US, as well as other countries and regions.

As can be seen, the global economy derives less than .5% of its total value from Russian and Ukrainian trade flows. Similarly, exports of these countries amount to less than .5% of the total global economy. The US, meanwhile, does even less trade with Russian and Ukraine. In sum, this means Russian and Ukrainian economic activity has little to do with most countries’ economic well-being.

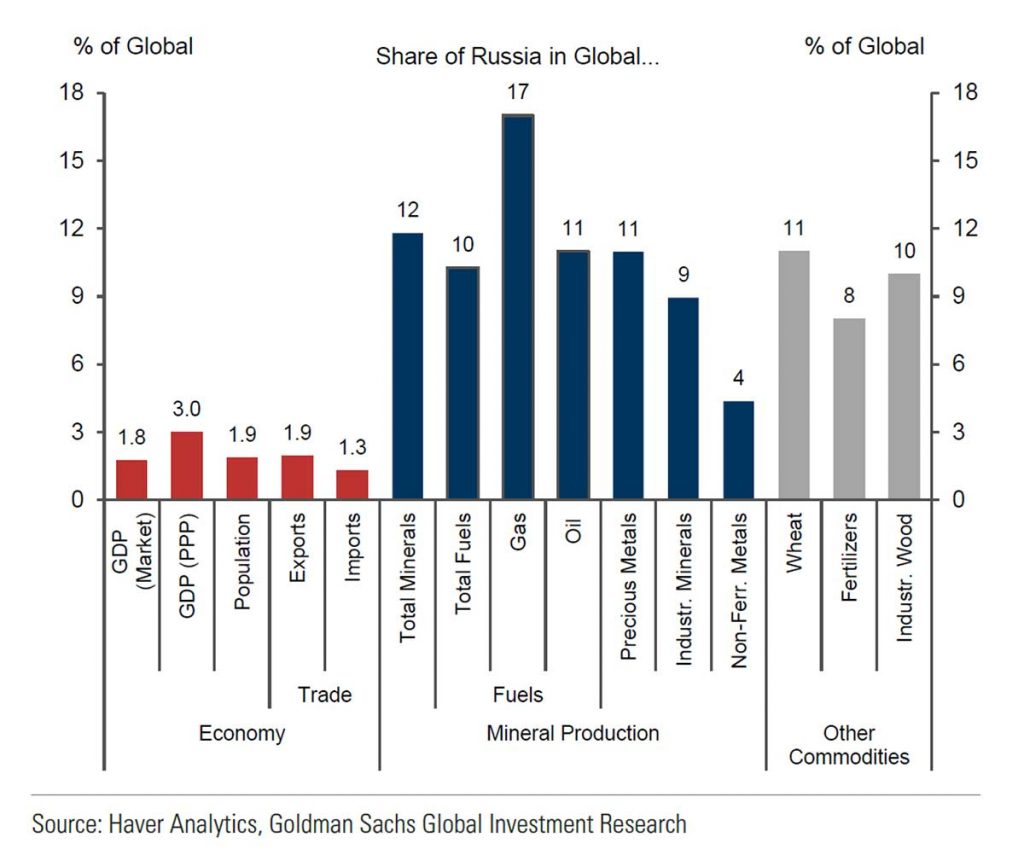

However, Russia can have a meaningful indirect economic effect on the whole world due to the fact that it supplies 11% and 17% of all global oil and gas. The war has already disrupted supply, which is why the price of oil has jumped since Russia’s invasion. And, should this disruption continue, it will filter through and may increase overall global inflation in the comings weeks and months.

Europe is most vulnerable to disruptions, as they purchase approximately 20% of their gas from Russia. As such, this Ukraine-Russia crisis could readily add at least .5% to Euro inflation this coming year. This would increase Goldman Sach’s forecast for the region to 5.5% inflation. Higher inflation, then, becomes a drag on spending, as not as many items can be purchased. Goldman estimates this inflation will shave another .25% off of Euro economic growth across 2022 and 2023. This crisis could cause similar reductions in economic growth in the US. However, the reduction could later be reversed as commodity supplies normalize.

In addition to oil and gas, there are other commodities, such as wheat and precious metals, for which Russia is a large global provider. Ukraine also provides much of the world’s wheat supply; in fact, together Ukraine and Russia provide roughly 25% of wheat globally. It is also estimated that Ukraine provides more than 20% of the world’s corn supply. Thus, the current disruption to these commodity supplies will likely create material food inflation globally, though less so for the US, as we source most of these items domestically. The below chart reports Russia’s share of various commodities more broadly:

Another indirect consequence of the conflict is possible rising interest rates, as central banks strive to limit the conflict’s impact on inflation. The US, however, was already on its way to start raising interest rates before the crisis. In fact, the FED could now become slightly less hawkish to limit economic downside, but it seems clear it must still start raising rates to thwart significant inflation the US has already experienced due to a combination of stimulus and pandemic-related supply disruptions. The FED is still likely, in my view, to raise its rate by at least .25% in its March meeting, and many times after that through the balance of the year. While inflation can possibly help companies earn more profits if they can pass enough of the cost on to consumers, higher interest rates can be a drag on profits, as well as cause a reduction in the value of stocks as a future dollar becomes worth less. In the short run, this often means stock prices are hurt, but in the long run, they can benefit.

Since stock markets are leading indicators, forecasting future economic activity, they have already fallen in anticipation of the indirect economic impacts outlined above. The drop, however, is certainly nothing like the global financial crisis where US stocks fell over 50% and the beginning of COVID-19 pandemic where equities dropped over 30%. As of right now, equities have thus far dropped close to 12% at the low point year-to-date (though markets had already fallen 5% by the end of January). Overall, the mood has become one of safety over risk-taking. That is, fear is trumping greed. During such times, there is often an opportunity. As Warren Buffet famously said:

Be fearful when others are greedy. Be greedy when others are fearful

Warren Buffet

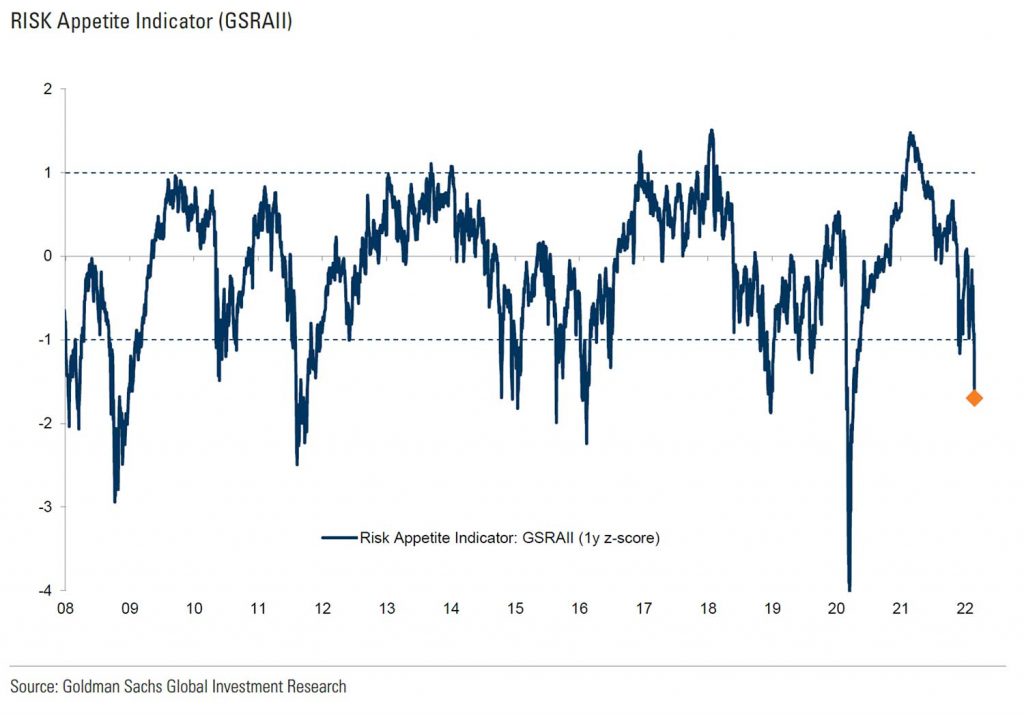

We can more rigorously assess how fearful or greedy people are feeling based on various market indicators. Below is one from Goldman Sachs, which shows investor risk appetite since 2008:

A positive number on the chart means (roughly) more greed than fear among investors, and vice versa for negative numbers. Warren Buffet was right: when these numbers turn negative (i.e., more fear than greed), the likelihood of stocks making money the next 12 months increases, as well as the degree of expected return. For example, at current levels, the next 12 months of stock return is expected to be over 15% and there is over an 80% chance stocks will make money. Nonetheless, there is a still a lot of uncertainty, so I expect a very choppy path for equity markets in the near term.

What should we do about it, financially speaking?

Based on the current level of fear, it would be suggested, at a minimum, to stay the course in equities. There is an interesting analog to this idea in soccer goalkeeping:

Statistically, the best penalty kick strategy for a goalie is to stay put. However, in practice they jump left or right 94% of the time. This is driven by the sense that they need to do something. (Source: The New York Times Magazine, “Goalkeeper Science”, 2008.)

The primary reason, at least for now, that there are not many things we should do, is that we have already laid a foundation to help us in times like this. Here are the three key risk management strategies we have been following for some time now:

1) Core Investing: rather than trying to identify the winning stocks, we invest in whole baskets of stocks. In particular, we utilize a core portfolio of passive and engineered passive investments that grab the whole market return through various liquid mutual funds and ETFs.

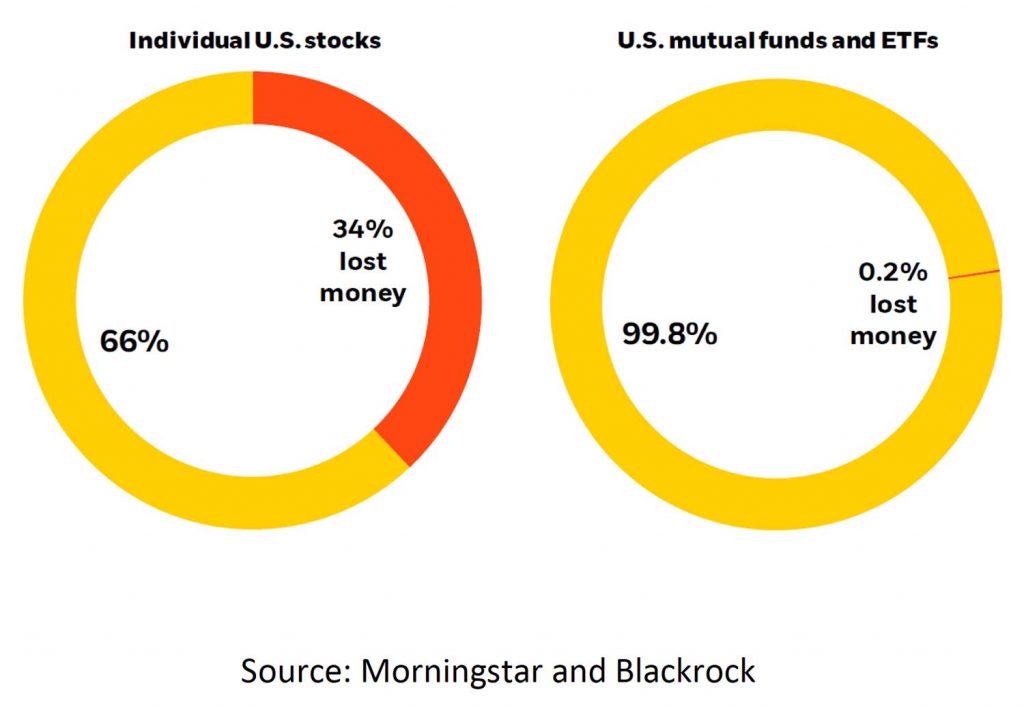

To illustrate how this approach helps with risk, consider the five-year period through 2020: If you invested in individual US stocks, you would need to be careful, as 1 out of 3 lost money after five years. That is, a random pick had a 34% chance of losing money, even after five years. Remarkably only .2% of all US mutual funds and ETFs had lost money after five years. And there are a lot of poor mutual funds and ETFs. This phenomenon is called active risk diversification, and it is one of our core tenants to properly manage risk. We certainly want to be on a 99.8% success rate path over a 66% one.

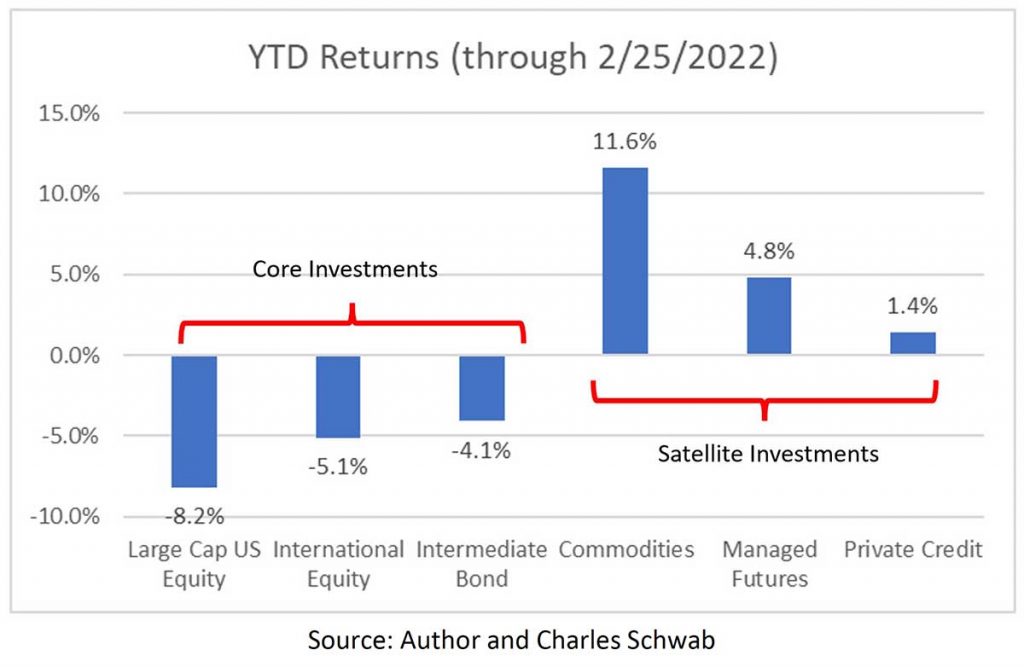

2) Satellite Investing: to further improve risk-and-return dynamics, we then build a satellite of alternative investments around our core market investments. These investments include such things as managed futures, commodities, and private investments. These are investments that large institutions use to provide an opportunity for returns when markets have lackluster returns or are even losing money. The below chart shows what this has looked like this year with some of our representative investments:

As expected, core investments, which most individual investors focus on, are down 4-8% year-to-date. However, we also use more sophisticated satellite investments that do not move in lock step to common investments. In fact, these investments are actually up so far year-to-date. To be sure, the majority of our clients’ monies are allocated to core assets (i.e., hence the name core). However, most Omega portfolios have 20-40% in satellite investments. Thus, as long as one is not distributing most of their portfolio this year, we can access more favorable asset classes to minimize the impact of adverse returns.

3) Strategic Rebalancing and tax harvesting: having both a core and satellite portfolio mix allows us to rebalance portfolios in a way that is not possible if we only invested in core assets, as do most individual investors. In particular, as seen this year, these two categories are often out of sync, providing an opportunity to sell one high and buy the other low. At the same time, we can also often harvest tax losses along the way. Historically, though not a guarantee of any future period, the former strategy can add 1-2% extra annualized return across time while reducing risk and the latter strategy can increase return by over 1% per annum while reducing taxes. Mathematically, the more different the investments, the greater the value creation.

We can never precisely know what is going to happen in these coming months of madness. We do know, however, that there is going to be volatility and we do know that we will be watching closely to take advantage of opportunities as they arise. As always, should you have any questions or concerns, do not hesitate to reach out to us. Otherwise, we greatly look forward to our next visit together.